33 strong hypotheses from the time I tried – and succeeded – to change sector, almost double my income and move by the seaside

- Mila Petrova

- Mar 24, 2025

- 40 min read

Updated: Mar 28, 2025

When amidst the COVID-19 pandemic I was being made redundant from a job I loved at a university which will forever remain ‘my university’ (Cambridge), I didn’t move a finger to seek redeployment. The simple process described in clear, well laid-out emails didn’t make sense. Something in me had checked out of this kind of life.

Decades ago, when my mum – a single mum of two kids at university – was fired from her inspectorate of education job on corruption charges (if you would have come to our house at the time, you would have been on the floor - linoleum floor - laughing and crying at the absurdity of the charge), she first filed a court case and then became self-employed. She often says they did her a favour by firing her. She’s long been in the top 10% of earners in the country and emanates a love of life and youthfulness you rarely see in those in their 30s, let alone their 70s. I somehow always expected that one day I’ll write my own version of her story. The opening lines had arrived: “How being made redundant from Cambridge in the midst of the COVID-19 job market crash with the equivalent of a 7-weeks’ salary for 7 years of service (yes, 1 month and 3 weeks) was one of the best things that has happened in my life”.

I love the quest for knowledge. I love research of the hard-core kind. Seeking knowledge is a need and an instinct that goes down to my bone marrow and out of the rims of my fingernails. This is one of the aspects of me without which there would be no me. But doing research, or academic research, is not the only credible way to seek knowledge. I was particularly missing the intensity of the emotional. I was missing playing with the mud of the messy human world that needs repair. Doing more work in global health, humanitarian and development research (or not necessarily research), and psychotherapy/ counselling (that’s what I studied for) was part of the vague plan. This is where the ‘change sector’ decision came from.

The ‘double my income’ decision was more gradual and meandering. Sadder too. It emerged from the sobering realisation that, certain disclaimers added, I had lost the love of my life (up to that point, hopefully not up to any point) to money. This extra-special man, who had courage for what most of us would shit ourselves around, had a profound, pathological fear of daily insecurity and profound, pathological need to own a house. In contrast, my life as a researcher was the epitome of the insecure and property-ladder-incongruent.

I’ve had 20-25 contracts for 13 years in two academic institutions (apologies for the broad range coming from a researcher, I stopped counting in 2017). I didn’t have a penny saved (the university pays averagely while Cambridge often comes second as the most expensive city in the UK, especially when you first arrive with PhD debt and a part-time job). I moved a lot, up to the level of writing a book about it.

I had accepted insecurity and renting as quite all right for this stage of my life. They were freaking my then boyfriend out. Ultimately, he chose to be with a woman he kind-of-loved rather than true-loved but who led a life that didn’t freak him out. She was earning 90K per year and owned a house of above the half a million mark.

For the first time in my life, I had a reason to infuse the goal of earning money with meaning and with passion. If money had cost me love, I SHALL learn to earn money. I even had a rough numerical goal. Obviously, I knew it was a problematic desire, thus put. Take it to extremes and I was going to have my version of “The Great Gatsby”, badly written. But it was a most helpful way to ask for what I can easily ask for, relative to the skills I’ve amassed, and put an end to struggling with the basics of life.

I have, by now, doubled my earning potential, changed sector, and moved by the seaside (in the opposite order; I won’t be telling you about the seaside goal, not least because I find it largely self-explanatory). I’ve worked on magnificent projects since then, including with the World Health Organization, a teenage times dream. I don’t have the confidence that my rather unnerving contract breaks from the time I will be telling you about below are over. I still work more hours than I am paid for. I still only rent my place (yet it is one with sea views). But while, until recently, I needed to change the course of my ship constantly and it was painful, I only need to maintain the course I am on now. I need to pray for winds in the right direction, not to be regularly spitting out salty, bitter, foaming water from moments I am almost drowning.

Below are 33 of the hypotheses about improving your job fortunes and your life, and about the realities of the process, which I developed while changing course. I call them ‘strong hypotheses’ because I’ve tested them harshly and they stood firm continuously. But they aren’t laws. They are valid for some people some of the time, though perhaps for more people for more of the time than standard job searching advice may make us believe.

My hypotheses may be particularly relevant to early-mid or mid-career people in the knowledge economy who have a lot to show for their years of work, are trying to make a meaningful leap in hard times, or even in normal times, but do not have much savings to allow them relaxed experiments.

Here they go.

1. Making a meaningful leap in your job fortunes can tear you apart so brutally that you will feel, from the bottom of your heart, why most people remain stuck rather than dare to make a change.

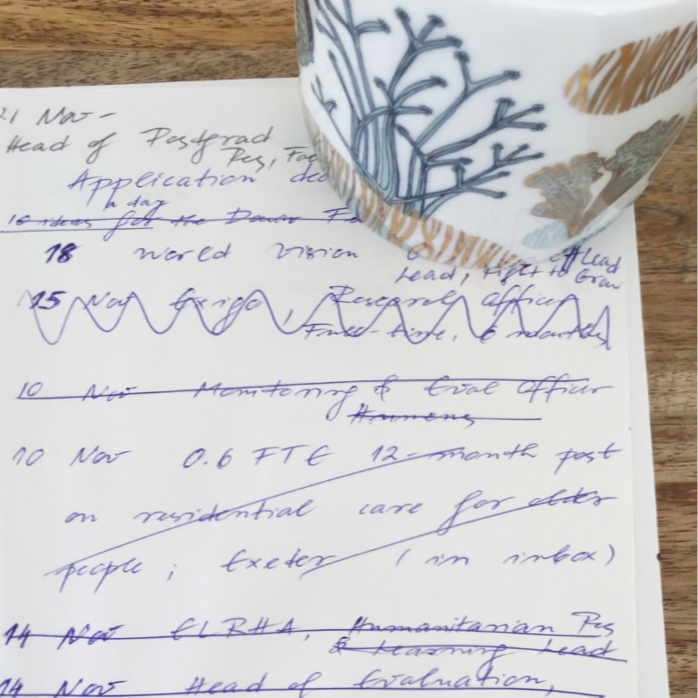

My Universal Credit account (yes, I got to the point of claiming benefits, more on that later) has the records of 41 applications over three and a half months, one of which the largely dead in terms of job adverts December. Since the total time I was unemployed was around 14 months spread over 20 months, I assume the total of my applications is over 150, possibly over 200, considering that I was frantically applying in the months prior to becoming unemployed, too. I’d say around 85% of the first half of my applications were seriously customised (with later ones, I already had plenty of ready write-ups). I used to work on a cover letter for the better part of a day (it took time to explore the company too, not only to adapt the description of my experience) and on a study design for 3-5 days (many research consultancies require that). My CV was a constant work in progress until only recently.

My bank account still carries consequences of having, at one point, borrowed money that were equal to half of my previous yearly salary. I’ll pay off what I still owe. I have almost doubled my earnings without changing my spending habits that much. But yes, with six university degrees and relentless applications, I got to the point of needing food vouchers. The moment I was offered one of the contracts I enjoyed the most and which cleared much of my debt, I was on the train to the airport to go back at my mum’s as I didn’t have money for food the following week.

I moved back to sharing a house. In my 40s.

I had cried at a job seeker’s appointment (come to think of it, quite an achievement to have cried in public only once, relative to the pressure I felt under and how quick to tears I am).

On month 5 of being unemployed, when I had also just moved to Cornwall, where I knew nobody, and was also in a 14-day post-travel COVID-19 quarantine, the only way in which I could fall asleep for about a month was with herbal sleeping pills. I’ve spent decades perfecting methods of dealing with the dramas of life, of which I’ve had a reasonable share, and with the anxiety they can trigger. Nothing of my well-honed, psychology-degrees informed, personally perfected tricks of the mental, breathing, writing, physical exhaustion, guided meditations and what not kind could help me enough.

It never got that bad after this experience. If anything, next time when I had a big gap between contracts and my finances were reaching food bank lows again, I was consistently in a remarkably good mood, up to elated. I was confident I’d work it out and that it can’t get as bad as last time. (It didn’t occur to me that the joy might have been an overcompensation as opposed to wisdom and resilience until a friend pointed it out!) But moments I’ve had. One of the clearest I remember was talking on the phone to my mum and telling her in a steely voice of determination, anger and controlled pain that I know why most people talk they want to change something in their life and job, make a leap towards what makes their hearts sing, but won’t do it, will only talk. Because it is BLOODY HARD. When the leap is meaningful, it is usually bloody hard.

2. Being single or having an incredibly supportive partner may make it or break it.

One of the key contextual reasons which allowed me to stick to the line in the sand I had drawn was that I was a household of my own, be it in a shared house. With all my commitment to following a path of my own, relationships mean the world to me. If I had a partner and had sensed even a tinge of anxiety of how long it was taking me, I would have backed down. I would have immediately made the choice I was refusing to make – apply for an academic job in one of my areas of expertise, almost anywhere in the UK. In fact, the plan before I had the change sector – double income – move by the seaside plan and which was made while I was envisaging a future with my then boyfriend was to find a job as soon as possible. Realistically, I was going to do exactly what I was refusing to do now.

Never resent the moments when you are by yourself. They give you the freedom to become more of who you are so as to be with those who are the ones for you. Alternatively, you need the person by your side to be somebody who’ll support you full-heartedly in your leaps, even weave some of the net to catch you while falling. Tall order.

3. Having work while not having a job helps. As does believing in work you once believed in, not because you feel the beliefs are true but because you trust in yourself to have once checked thoroughly that they are true.

As some of you are painfully, resentfully aware, academic studies are never completed within the timeframe they are supposed to be completed. There are always papers to write or revise after your funding has come to an end. I had plenty of research wrapping-up to do while looking for a job. Let alone that looking for a job is a full-time job.

As I couldn’t work from my (shared) house, I was renting a desk in a co-working space. This, in combination with the above, meant that I was out of bed into the office every morning of the working week (on weekends, I was training myself out of the habit of working on weekends and was ‘obliged’ to go on an adventure somewhere in Cornwall). I’ve not had a single day feeling I had no reason to get out of bed because I didn’t have a job and because my in-bed-phone-scrolling was showing me nothing to apply for and because life was so uncertain and scary that I’d better hide under the duvet. It doesn’t mean my emotions weren’t running wild, as I’ve already written, but not in a stay-in-bed way.

My compulsion to complete what I’ve started may be strong, and I may have been lucky to have meaningful old work to engage me, but this was a self-instruction too. When my mind was screaming how close to the upper limit of my overdraft I was, how I cannot see anything to apply for, how irrelevant my skills have become, how I am on the receiving end of silence after silence … I had to “focus either on your creative work (the book I was writing/ editing) or service to the world (the studies in humanitarian and development contexts I was supporting)”. No debate allowed. No wildly running emotions. Sit yourself down to do the work.

The worst my job and earning prospects looked, the deeper I immersed myself into work I once believed in and of which I once believed I was good at. I had no connection to those positive beliefs on sitting myself down to do the work. I commanded myself. I ignored the lack of motivation and emotions of the right kind. But I would always emerge out of a session reconnected to them.

4. For a long, long time, you won’t know what you want, you’ll be excited to have the freedom to experiment and learn, and you’ll also REALLY need a job, so you’ll be shooting all over the place.

The hierarchical levels I applied at ranged from that of a receptionist to that of a Director of Research. The themes and nature of the jobs varied from mine action (mines that explode, be it on the research side), through eating disorders (as a psychologist), to writing the digital health strategy of Laos PDR (got invited for an interview, if you thought me over-reaching). The values of the organisations oscillated between unsentimentally mercenary to openly Christian. The randomness of alternatives outside the above examples was just as impressive.

For most of us who decide to make a substantial change in their career driven by external circumstances, even if matching a call of our soul for something different, the shape of our better job is rather undefined for a start. It is clarified through the process.

While I was willing to change research topics, I realised that health, healthcare and human well-being still held a lot for me. I needed a twist but not a new field.

While I was keen to do more psychological work in the health service, I gradually realised that my most natural clients are people who already do a lot of self-exploration and would pay for a private practitioner rather than wait for a year and a half for 6 to 12 sessions of CBT (which is not my favourite modality of therapy anyway).

While I enjoyed the romantic fantasy of how fun it would be to do, for a part of the week, low-level admin work to get a feel for a new environment (e.g. the probation service) and take a break from responsibility, I realised I am past the point when I would happily do what I’m told and smile on top. I want to have the voice and contribution of the higher hierarchical levels.

While some of the managerial jobs I’ve seen had a portfolio that was more exhilaratingly varied than any researcher’s or psychologist’s job could have, I realised that the day-to-day tasks of a manager (such as switching from meeting to meeting, leaning on people or tracking progress in project management software) not only do not excite me but dry my very soul. I need my one-to-one explorations of the human soul and solitary digging into data and ideas (and some team meetings) to feel on fire. I also believe in only working with people who do their job without being prodded to do it.

All the above is an ‘of course’ for me now. Yet it emerged slowly. If you are in a similar position, it will emerge slowly for you too. It is clarified through the applications, especially in writing the cover letters. When you can’t persuade yourself in your own motivation or suitability, you shift the inner landscape a little, even if in that moment you submit the application. It is fortified through the successes, both through how we feel about the offers and in our new jobs. It is sharpened through the failures – whether they were a shoulder shrug or made us seek insider information and external pairs of eyes and seminars and training and books and posts so that we try again and again and again until we are in.

At some point I also reached the rather fundamental insight that there was something that mattered way more than the above circles of preference. I’ve always loved the jobs I’ve been in (not counting the only one in over 15 years I’ve left within a few months). I’ve been judicious in applying and I’ve been lucky, true. But I also carry myself through jobs, themes, teams and organisations. I am the biggest constant and the most important factor in a job.

Who you are and how you do what you do will always be far more important than what you do and where you are doing it.

5. It is easier to cut the cord between rejection thoughts and feelings and your actions than to tame the thoughts and feelings.

Many, if not most of us feel and conceptualise the experience of job applications leading to nothing as a rejection. Dent after dent, such rejections batter our perception of being good enough, possibly a fragile one to start with anyway. It is as if somebody looked at our experience and crossed away the pages with a thick red marker. Laughed at us. Saw a red flag we can’t ourselves see. The hole in our experience we tried so glibly-or-not-so-glibly to cover and judged us for the clumsy attempt.

We can also start catastrophising the positioning of our skills in the brave new world, or simply the world outside of our former organisation or sector. I have skills which were once precious but are no longer valued. I have skills which are still valued but expensive, nobody wants to pay at the level of their top-notch version. I am becoming obsolete in a world of machine learning and AI. I have skills which are only valued in the sector I want to leave. I am making a systematic error in my approach (even if we constantly adjust our approach).

As it happens, it was precisely the accumulation of rejections which allowed me to catch glimpses of the irrationality of the framing. From around application No 16, I started thinking that yes, I may not be good enough for the individual jobs I’ve been applying for, but I’m good enough across them as a logical average outcome. I am a super hard and responsible worker. Come to think of it, anyone who has worked with me for long enough has explicitly said they’d love, hope, will seek ways to work with me again. It was not true that I couldn’t do any of the jobs I applied for in those 16 applications. I can. I CAN.

I currently prefer to reconceptualise ‘rejections’ through a network of four concepts: being ‘unseen’, ‘the bright light of another’, ‘the mould’ and the ‘many winners amongst the losers’.

Most of the time, a rejection of one’s application bears no resemblance to a rejection. Most of the time, nobody is there with a thick red marker and a desire to humiliate you. Rather, our application became invisible. Somebody else shone brightly relative to what was sought for the post. Somebody else shone brightly because that’s what happens when an applicant slots into the mould for the job perfectly. Flashing lights! It’s a match!

Importantly, moulds are incompletely fleshed out in any set of essential and desirable criteria. They are insensitive to the beauty outside of them too (if anything, the more there is outside the mould, the more concerning it becomes that you’ll run away at the first opportune moment or rise to oust those currently recruiting you). And yes, moulds are sectorial, contextual, organisational, thematic, linguistic and many more and you are an outsider to that new environment, even if an outsider it needs to be enriched and expanded by. As a recruiting manager bemoaned recently, in relation to a process I was not participating in, you don’t have the legal tools to recruit for such as-if irrelevant brilliance because you can’t demonstrate a fair process if you don’t recruit as close as possible to the advertised criteria.

Rejections don’t mean you weren’t a killer candidate either. As Roy Lilley (whose daily e-letter on matters NHS, the UK National Health Service, apparently reaches 300,000 inboxes) once put it, there are many winners amongst the losers. There are exceptional candidates amongst the ones being rejected, often including you.

A rejection conceptualisation may be self-centred, dramatic, paranoid and catastrophic, but it is as natural as it gets. I lined up my current network of concepts only after I got a WHO consultancy as the last (wo)man standing in a competition of around 300 candidates. I could not switch off the ‘rejection’, ‘not good enough’, ‘systematic error’ and similar thoughts before I got solid proofs against them. Oh, no. I believed them. As far as emotions went, I believed them fully. But I had the rational awareness that their justification was incomplete, even if the emotion was full on.

What saved me from digging a hole for myself, what has always saved me when it comes to negative thoughts about myself, is that I deny them access to my actions and non-actions. Yeah, all right, I believe you. I’ve not been able to silence and change you in spite of my persistent, earnest attempts over the years. But I can cut the cord to my actions you are trying to throw in and hook on. My actions will be fuelled by other beliefs.

If we don’t put a barrier between feelings of rejection and our actions, we will dig a hole for ourselves with a spade made of thin air, then fall in it. As it is a hole which destroys self-esteem, agency and, more broadly, mental health, there is the grim likelihood that it punctuates our life for the worse – and forever.

6. You will be pulled by the past again and again, even if it looks like nothing you’ve ever done before.

Your past career choices won’t let you off easily. The reasons are more than the deep grooves they’ve carved on your CV.

The most mundane way of your professional past pulling you back is through the basic automatisms of job searching – the websites you use (and don’t tell me online habits are easy to change) and the leads you’ll be getting from your network.

The job searching websites I currently check are just as natural as www.jobs.ac.uk once was (the only UK site you need if you are looking for an academic job), but they didn’t appear right away. It may well have been a few months into being unemployed that I found DevelopmentAid and, as weird as it sounds, even the WHO website and alerts. It was a year and a half after I became unemployed that I even heard, in a random conversation with a lovely hyperactive guy who makes your heart glow but may be difficult to understand, about IR35 working. (Do you know of IR35? You see the point. The awareness came a year and a half into needing it, through a single conversation, and one that was hard to follow.)

The past also pulls you through jobs that make you feel you’ll be perfection incarnate. There were several jobs, particularly in palliative and end of life care research outside of an academic context, for which I fulfilled the requirements with bells and whistles, and then more. There is something irresistibly sweet about slotting into a job in which you’ll feel a Goddess, a saviour, and the undisputed authority in one. But ‘slot into a job’ often means no stretching, minimal development. You weren’t looking for comfort and admiration.

The most treacherous and consistent way in which the past pulls you, however, is by you going for less than the ‘all’ that you had committed to and not even noticing you’ve done it again. I had to change sector AND improve my earning capacity meaningfully, while not compromising on any of my usual criteria for a job (exceptionally interesting, having an important cause, minimally shaped so that I can shape it, etc.). I still applied, more times than I wish to admit, for roles that fitted all other criteria but were below my latest pay grade, sometimes almost doubly so.

I even accepted such jobs on two occasions before pulling out. I find it very difficult to disappoint people and waste their time. It was a mistake to apply. It was a mistake to accept. But make them I did. At least I didn’t make the mistake of starting.

When the pull of the past and pragmatics of the present combine, ‘temporary’ solutions are sensibly stepping forward. Yet if you allow the past to ‘temporarily’ fill in the void you have opened to create the future, you remain stuck in the past. If you don’t put up with far more of the void than is comfortable, you’ll never pull away.

7. The repetition of what you have done in your professional life will both give it a reality you will begin to embody and make it sound hollow, even feel a blatant lie.

Repeatedly writing of what I have done, achieved and can do gave it a reality, solidity, expansiveness that, at times, impressed even me. It gave me confidence I didn’t have at the start of the process. I sometimes wonder if ‘the divine plan’ was not to stay without a job for so long so that I can finally begin to appreciate my experience, as opposed to live in a never-enough constant-comparison so-much-more-to-learn mode.

At other times, that same repetition made the sentences devoid of meaning, especially against the backdrop of deafening silence from recruiters. ‘Sought for methodological advice and supervision from four continents?’ Ha. They didn’t seek you. They sought your institution. Also, are you even sure? Do you even know how many continents there are?

I was reassured that the sense of irreality, even of lying about my own experience, was normal when my cousin shared an identical inner conversation: Fake! Impostor! Why are you at home when you’ve had the world in your pocket then?

Remind yourself that a fact is a fact. It helps to have an uncompromising rule for nothing but facts on your CV and to take the time to collate the hard-to-collate metrics. Then you know that if something is there, it is true, even if it is hard to believe it in a moment of suspended reality.

8. The inner money ceilings are a big thing until they aren’t. Then this is what you expect to be paid, story over.

In the first days of the first consultancy that paid four times what I was used to receiving in academia (although, as I soon found out, it was closer to twice more once taxed), I was repeatedly checking if my hair had turned greyer overnight. I don’t say it metaphorically. I feared that if I’m paid that much to do the research tasks I loved the most and found so easy to do, then I was not doing something I was expected to be doing.

What added to the inner turmoil was that I was seeing one of the most incredible datasets I would ever see in my life handled through an analysis driven by the (expensive) software the team had purchased and been trained in rather than by the questions the project needed answered and the nature of the data. For me, the data was going to waste. I had one month to turn around the waste and I couldn’t see how. Yet I had to. Because why would anyone pay me four times more than what I would be paid under normal circumstances if they don’t want something verging on the impossible? Or unless they were seeking a scapegoat consultant? (They wanted none of the above. They simply didn’t know better.)

This pattern of doubting my skills in light of what I was being paid for them was triggered persistently in my transition out of the academic sector. I was paid so much more, yet I was doing the same work. I was working shorter hours and hardly ever on weekends, as people were clocking out incomparably more reliably than in academia. The workload felt lighter as projects rarely hung over you for years, sometimes not far from decades. The pace was faster but not that much faster. If anything, it felt there was a lot of useless urgency everybody was being sucked in. The quality was lower, but when the work was mine, I’d still say it was the best we could have done in the time we had and reliable enough for the uses it was needed for. It is not as if I felt I was paid to compromise my scientific integrity (I can’t).

I now attribute the higher pay to the higher stakes in the contexts I was entering. These are more directly linked to policy making and practice; more responsive to politics and influence, including in framing your evidence and conclusions; more likely to throw your planning out of the window without you having the option of arguing for the importance of the important over the urgent; less egalitarian; more demanding on judgement of what good research practice steps to skip without compromising quality … For these, and many other reasons, some sectors pay far more for rather mundane, even low-level, research skills than academia does.

I no longer ponder over the reasons for the pay difference. I’ve crossed the inner threshold. Now I see no reason to be paid less than I’ve been paid so far. My job is to do my work in a way so that those who pay me believe it is some of their best spent money. And I continue to work as I’ve always done, meaning that how much I’m paid and whether I’m paid at all is irrelevant to how I do the work. I also accept commitments guided by the same logic. I ask myself if I would be prepared to do a piece of work for free if money weren’t an issue. Only now when I say ‘yes’ to the work, I add a definite ‘yes’ to the money too.

9. In your new sector, you are an alien. They’ll avoid you like the plague until they really can’t sort it out without your alien help. (Relevant if you are changing from the sector which trains, nurtures and innovates widely in a particular skills set to a sector which simply uses it.)

If I can generalise from my specific corner, there seem to be two classic ways in which the sectors which simply use a particular skills set relate to the sectors that train, nurture and innovate widely within that skills set: 1) assert a specialness and hence an exemption from best practices and 2) fear being judged. At every interview for a research post outside of academia I’ve had and at almost every meeting in a new role, colleagues either assert that their way of doing research is ‘operational’ rather than ‘academic’ (‘we don’t need it, and don’t have the time, for that level of precision and detail’) or, alternatively, worry how I’ll judge them for the non-rigorous, at times unacceptable, things they do (e.g. backfilling the evidence after deciding what they will say or do). The third classic, which may be specific to perceiving academics though, is that I’ve led a ‘sheltered life’, that there are many things about the uppercuts and frantic pace of ‘the real world’ I am unaware of.

Such stereotypes are grossly unfair on me and on a proportion of my academic colleagues but, as any stereotype, they are valid enough to survive. If you too are exiting a sector which trains, nurtures and innovates widely in a particular skills set and moving towards one which only uses that skills set, I bet you too will suffer from a sector-specific version of such stereotypes.

When you first try to land in a new field, you are an alien. Your space shuttles feel scary, superfluous, romantic. Normal planes are enough, better. Your skin looks too soft. They don’t want you moaning of sunburn on Day 2. Of course, it is also true that your big feet will step on plenty of toes along the way and some of the things you will say will be totally inappropriate. It is also true that you are unprepared in many respects, which makes you a liability until you learn, until somebody is prepared to teach you.

There are good reasons to be treated with suspicion. Just don’t make them your own. Stay grounded in the good will and the super tools that you bring. Tie back your ears. Cut down your toenails. There will come a time when people will be queuing for a ride on your spaceshuttle.

10. Transferable skills don’t matter unless …

I know this goes against fundamental job searching advice. Relative to my experiments, transferrable skills don’t matter for jobs in that expansive zone between post-entry level and senior level. Transferable skills matter there if you are killing it on an essential requirement (e.g. 16 years of research experience, 8 years of work in digital health and innovation implementation, a PhD on whatever), yet are still not enough. By transferable skills I even mean methodological skills acquired in a different thematic context.

Theoretically, it shouldn’t matter if I’ve learnt user research in the health sector or the criminal justice system. But it matters. I am still to be invited for an interview in a thematic area I have not worked in.

The greatest gap I’ve crossed was in being offered a project on workplace relations while coming from a health research career. But I also have a degree in Work and Organisational Psychology. I have worked in HR. I have researched new professional roles in the health sector. Perhaps more than anything though, the recruiting manager had herself changed sector radically. Thanks to her transferable skills.

11. You won’t realise how good you are until somebody recognises it for you.

With the eyes of self-compassion, I would say that the vibe of my early cover letters would be endearing if it weren’t so self-defeating: I really want to work for you, and there are some good and useful things I’ve done, please, please let me come and learn and I’ll do my part! They create the image of somebody conscientious, responsible, hard-working, accomplished but also not quite having what it takes.

I certainly didn’t feel I had what it takes for those new contexts, even though I didn’t have a speck of a doubt that I’ll double down and learn. I always double down and learn. When I was first looking for a job outside academia, I semi-consciously believed that the ‘other sectors’ have also grown super well trained researchers, be it through their own pathways. So my colleagues and competition there would be both super well trained in all the methodological skills I had AND context-relevant.

Well, NO. Of course, our new colleagues and competition will know countless things you and I don’t know. But, still, academia is the place where sublime research skills are nurtured; the IT sector is where sublime IT skills are nurtured; the circus is where sublime trapeze performance skills are nurtured, etc.

In the context you are coming from, many of your skills are taken for granted. They are also persistently not enough. There is something new coming daily. There is somebody who can do what you can do with a beauty and alacrity that thrill and despair you in equal measure. In such an environment, you forget all the hard work and the years and repetitive daily actions and potentially millions of minute iterations that have gone into honing your skills. You don’t see them until somebody else makes a comment about them. If you too are somewhere early mid-career or later, you’ve also had plenty of time to normalise what you have learnt. The deafening silence and rejections in applications also make the thought that you are good a rather dubious belief.

I needed to hear, from the outside, ‘how much you’ve done’, ‘how impressive your profile is’, ‘I need to escalate to the Board as I can’t advise on improving a CV like yours’, and a few ‘wows’ to begin to see that my experience and achievements were not average. I’d say it took about nine months to hear a comment that showed sincere admiration from people who didn’t know me and whose criteria I could trust (even though they still chose somebody else). Sometimes the better you are, the longer it takes to hear such compliments. The people in a position to make them may fear sounding either patronising or childish in their admiration or, alternatively, be too busy comparing themselves to you.

There are contexts where the ‘you are good’ signals are totally lacking because of the nature of the signalling system, not because of a weak signal.

I trust you won’t now tip into illusions of grandiosity.

12. ‘Reaching out’ without an ad is not worth the effort.

This is another parameter where the evidence of my own life went against much advice, unless that advice is given in the (implied) context of yet another numbers game. I’d probably sent over 30 such emails, including ones offering my post-PhD-level research skills for free in exchange of being taught something practical.

To the emails I sent to non-contacts (the majority), I received two responses. One was to tell me that my profile was amazing but they had no money (fair enough). The other was to tell me that my profile was amazing but they had no time to take me on board as a volunteer. As sad and ridiculous as it is, most organisations that desperately need extra pairs of hands do not have the capacity to absorb the help offered.

13. Even if you are a specialist in advising others on how to present their experience, you will fail to see the flaws in presenting yours.

As I mentioned, one of my MAs is in Work and Organisational Psychology. I have worked (briefly) in HR. I used to follow trends in the sector daily. I know how to write a CV. I know how to advise people to write their CVs. I have had people find jobs days after I’ve helped them edit their CVs. I was nonetheless blind to how my own looked. If it wasn’t for George, a good old friend, who irritated me with his advice on numerous things that needed changing, my recent job trajectory may have been quite different.

When you have done and lived something, you often cannot see how inadequate the words you use to express it are. To you, what you say has depth, richness, nuance, glory. You only mention the tip of the iceberg and continue to see the iceberg. Others don’t. Nor do they crash into you. They glide past you.

14. How you feel after an interview bears no relationship to the offer.

There have been several interviews after which I’ve said, “It went really well. I couldn’t have asked myself for more”. I never got a job after such interviews.

For half of the jobs I was offered, I thought that the interviews went reasonably well but also that I’d messed up or forgotten to say crucial things. I do not see a direct relationship between interview performance and outcome. I seem to get an offer if I like the people in my gut and heart (and liking is often a mutual thing) and if I feel comfortable in the interview, even if I don’t give the best answers to all questions. (That’s, obviously, on top of being an excellent fit for the post.)

I will add a mini-hypothesis. In my experience, solid confidence at interviews is either over-rated or doesn’t look good on me. Interviews I felt truly confident in, where I knew I was good for the job but could also take it or leave it (a feature of confidence but also of a weaker desire) were never followed by an offer. I don’t think I come across as arrogant easily (the feedback decades of life have returned to me is far more along the lines of friendly and approachable) but I either occasionally project a cold edge of arrogance, even if I feel nothing like it on the inside, or solid confidence does not suit me. Somebody who is good at what they do, successful at what they do, and owns that can be quite a pain to have around, especially if a manager does not feel secure in their leadership and authority.

You can mess things up in an interview (up to a degree, of course) and even come across as insecure, and still get the job.

15. Going through interviews helps (much to my surprise).

I consistently objected against this familiar statement. Even after half a year of job searching, I could still experience dramatic bodily responses, up to intense shaking, prior to an interview. When ‘you really need to get this one’ because you are running out of money for food, ‘there will always be another chance’ is not an easy mental state to enter.

It seems that in those times I simply had not reached my personal threshold of becoming practised enough through interviews. The questions do, indeed, begin to repeat. You will even be bemused by the lack of creativity on the part of recruiters. You will crystallise your answers. Correct the self-defeating elements in them. You will also acquire the ‘all is good’ mindset. There will always be another chance, indeed.

16. Write for the common man/ woman, not your peers.

Also late in my job searching, listening to the presentation of a kind, grounded and meticulous HR woman, I was struck by the epiphany of how often I have been writing for the wrong type of audience. I have consistently tried to dazzle high-level managers and research-savvy colleagues. Yet the first person to see our applications will almost unfailingly be an HR person. For organisations where the competition is fierce, we may easily be falling out of the baskets at this first generalist stage.

I figured out I needed to be writing for the common man/ woman in three ways, at least as far as profile sections in online forms (as opposed to CVs) are concerned:

o Make each profile section a narrative, a story, something smooth and enjoyable to read. Don’t create a text that condenses the most information in the least number of words. Write the text that is smoothest to the brain.

o Tone down the technical language, even if you will need to preserve ‘the keywords’. It is almost absurd how committed I am to clarity in my academic writing, having an unbreakable rule that my papers should be accessible to any interested and educated person, and how technical and keywords-focused I could make my profiles and cover letters.

o Show yourself as the human being with their values, not only as the professional with their expertise, even if you need to rack your brain for persuasive examples. I’d probably never mentioned values and soft skills up that point in my profiles and cover letters. Those are nice empty words until you know me! Yet I challenged myself to think harder. Soft skills and values too have examples.

Following this epiphany, I immediately revised my WHO profile. By that point, I had nine applications in and one interview invite. I got three invites in the next couple of months, even had to decline one interview because I had already started a contract. My WHO consultancy also came shortly after those profile revisions.

Never underestimate the value of a smoothly running story and a relatable human being for a tired recruiter’s brain.

17. Fast and inspired works better than painstakingly crafted and thoughtful.

As infuriating as I found it, I got more responses to applications I had typed away in a mad rush than to ones I had painstakingly crafted. It started one evening when I was moaning to John, my lovely former landlord, that I either submit a job application or go to yoga. He told me I can absolutely knock an application out in the hour I had before yoga. I did, with great excitement at the outlandish idea. I got an interview a few weeks later.

There is something to be said about the naturalness of a rapidly written email/ cover letter. It comes from the same state of mind as the one in which it will be read. That said, speed is also possible because, by a certain point onwards, you have written all the descriptions for all possible roles for all possible combinations of profiles you will be applying for at this stage of your life.

18. Talking to nice encouraging managers is just that – talking to nice encouraging managers.

I have written or spoken to a few hiring managers to check if my somewhat unusual profile was of interest relative to the vision they had for the post. They have been unfailingly enthusiastic, supportive and welcoming of my application. With one exception, I have not even been shortlisted for an interview. The disconnect seems so stark that at least for one of the occasions I wonder if my application was not filed away at the level of HR selection, even though I had mentioned the conversation in the cover letter. One way or another, the evidence from my own life is that talking to a nice encouraging hiring manager is just that, talking to a nice encouraging hiring manger. It is no indicator whatsoever that, once the whole pool of candidates is in, you will still be of interest.

19. You shall be forgotten. 99% of the time, nobody reaches out because ‘they have kept you on file’.

When I look at my files and folders, I find that I do not have a speck of a memory of applying for some of the jobs I have applied for (and I am somebody who remembers plenty of useless things). Because of sheer numbers and low personal relevance, it must be incomparably worse for people who say they will keep you in mind for future opportunities. By the time such opportunities arise, the recruiters have FORGOTTEN you. Completely. No matter how wowed by your profile they were.

They may remember you if they have spoken to you in an interview or at least in an informal meeting. One of my closest and longish-term unemployed friends got her job like that many months after the original interview. But the profile-on-paper version of meeting you, exchanging some very positive emails, and having you on file? Even the average case of having met you? Gone from memory, baby, gone.

20. Half a decade of education in a field you have not worked directly in, even if you have it permeate all your being, will not get you anywhere.

While I have three degrees in psychology, have its theories and mindset permeate my research and everyday life, have done paid work way back, have done voluntary work more recently, consult friends and family and occasionally private clients as a matter of course, not a single time I have been shortlisted for the psychology-related jobs I have applied for. It doesn’t matter I have also had decades to develop transferrable skills (see also point 10.).

Your original education has no weight if it is now many years ago and the ways in which you stayed this person and professional are not formalised in job roles and titles. Formally, all my roles are researcher ones, even if I could not have been a researcher in the sensitive topics I have been researching if I weren’t a psychologist too, even if being a researcher has made me a far better psychologist too. I can easily turn this around and become an illustrious candidate if I add current voluntary experience or another diploma, if not necessarily a degree. Or I won’t bother. I am creating many of my roles by myself anyway.

21. Good manners have been lost from the recruitment world.

I don’t think I have received more than 25 emails to inform me that my application will not be taken forward. I am talking about the basic acknowledgement of where you are in a process, not feedback after an interview. While it is generally different if you’ve had an interview, even then you may need to be chasing recruiters to find out about the outcome (in my case it has been only once, but my friends, especially those working with headhunters, report of a startling regularity). As far as meaningful post-interview feedback is concerned, I’ve had that twice. On both occasions they were ‘glowing rejections’, as I call them – the feedback about your profile and interview is remarkably positive but somebody else has slotted into the job through previous experience far better. Though is this meaningful feedback? It feels wonderful but doesn’t teach you anything.

Silence is the norm of the day. Considering that the HR person or hiring manager on the other end is, like most of us, running four times faster than they wish only to stay in the same place, and that I regularly see jobs with 600+ candidates on LinkedIn, makes me understand. It is easy to solicit candidates. It can be easy to apply. Numbers become unmanageable.

Nonetheless, it is disheartening not to hear a word, or to receive the briefest, most formulaic email possible, when you’ve put in days of work in an application. I even believe that the companies that work out considerate rejections will be the ones to have the crème de la crème of candidates. In persons and in organisations, in unrequited human love and unrequited job love, one of the most attractive features is to be able to say ‘no’ kindly and gratefully.

22. There is further down than rock bottom.

On reading my diary entries for 2021 and early 2022, I was struck by how often I had written that, by XXX month, it is impossible not to have a job because, well, it is impossible, it has been ridiculously long, and because I cannot survive. Then there were the numerous times that I had written that NOW IT CANNOT NOT BE because the previous inconceivable timeline of nothing happening had come and gone again. It is astonishing how much further the search can drag on, how much deeper the financial hole you are digging for yourself can become. I am sure it applies to the emotional and identity disintegration too but, as I mentioned, with some exceptions, I managed to ward those off.

Rock bottom is elastic.

23. There is more support than you knew.

The other side of the above is that you may find far more support than you could have ever imagined available. One of the best things that happened to me in this period is finding a sense of being held by the World. I am not one of the lucky ones who have grown up with this sense of fundamental security. On the contrary. Yet the way in which support was appearing when it felt the crack I was standing right next to would engulf me – my mum sending me money unexpectedly, the taxpayer returning overpaid taxes from a previous period, a food voucher from a new programme, a conversation with my cousin helping me realise that people far more accomplished than me have been through the same experience – created a new sense of trust in the workings of the world. I wouldn’t want it to have been easier as this gift would have been unavailable then. Yes, as magical as that.

24. DWP (Department of Work and Pensions) staff in England are extraordinary.

While I find the level of payment for jobseekers in England outrageous – it was a little over £70 per week, when I was easily paying £700 per month of taxes and national insurance while earning – I will not be able to find enough words of praise for the compassion, professionalism, humanity, pragmatism, reliability and creativity of the DWP staff I’ve encountered.

What they said was also said in a way that made me listen. The first advisor I spoke to told me off with a strangely effective compassionate harshness that I should not be working for free for Cambridge for what was the fourth month running, that I should apply for Universal Credit, and I should take better care of myself. Simple, basic, grounded and effective for when my romantic values run too far ahead of their pragmatic counterparts. Thank you for the fixes of pragmatism and empathy, above all.

25. The most difficult decisions are yours.

When you hold with one hand an offer which gives you a secure path back, but you know that the point of the struggle was not to turn back, you really want to hear someone’s wise advice on what to choose. There are many more difficult decisions on such a journey but, ultimately, the difficult ones always boil down to how far do I continue, how much longer do I stay hanging in so that I get to where I am going? These decisions will always be yours.

I owe a heartfelt thank you to all my people who didn’t make it difficult for me to stick to the line in the sand I had drawn. They were frustratingly evasive in moments of hard decision making. Later, several of them told me that at certain junctions they would not have been able to decide as I decided, but they never told me to be sensible, to stop being naïve, to remember that compromises are part of life and so on. They often bought me time, through money, and offered me masses of emotional support, even though they could not offer me all the emotional support I needed. Not because theirs wasn’t A LOT. But because all the emotional support you need cannot come first and foremost from the outside.

26. You shall be taught compassion for the unemployed (even if you thought you had it).

I am responsive to human suffering. It is not a concept I engage with, but I meet all the criteria for an empath. Yet when it came to people out of a job, I used to have an appreciation that losing your job can be hard, that looking for a job can be hard and uncomfortable, but I would also think, roughly, that if you don’t have a job within a month or two of starting to look for one, then you don’t really want one. Or are doing something wrong.

I was taught compassion and non-judgement for the unemployed in a way I have not imagined I would be. Thank you for the lesson in kindness and humility, Life.

27. No-one is bigger than bread.

As you may have sensed, I believe in doing all it takes, until it takes, for as long as it takes (as Katrina Ruth would put it) and in not allowing compromise after I have reached the certainty that ‘gradual’ doesn’t work (a decade and a half of testing the gradual philosophy is, indeed, enough).

Yet there comes a point when even those like us begin to wonder if it is worth it. Because the void becomes so overpowering and deep that it begins to destroy you. Because life, after all, is good in numerous shapes and forms and it doesn’t need you to change sector, double your income, and move by the seaside for you to feel them. Because some of you, sometimes I am one of you, believe that there is a bigger plan and our intentions will not materialise now because we are being directed on a path which is better than anything we could have imagined.

What became my step-back signal was a saying in my mother tongue, “Nobody is bigger than bread”. The point when I had to admit that I was struggling to buy food, even with all the money I had borrowed, was the point when I decided I needed to put my sword and shield down. It was time to return to applying for academic jobs, accept a salary close to my previous one or with a tiny increase, and potentially move to a dark place in the North of England.

28. If you have put up a good fight, making a compromise is not a big deal. Take a gracious bow and exit (temporarily) without fear.

Simultaneously, I realised that this was not giving up. This was not a compromise of the usual kind. I had put up a good fight. The mental landscape had transformed. Nobody is bigger than bread and I needed to take care of my bread. I needed to re-group. But once I had done it, I would start again.

29. Choosing a ‘wild experiment’ rather than a compromise may refuel your confidence and love of life.

Simultaneously again, I decided that the temporary job I would take to survive will not be a compromise but, rather, a ‘wild experiment’. If I needed to earn money at a supermarket’s cashier desk, my soul would be dying with each packet of sugar or bag of potatoes I barcode-activate. Yet if I needed to earn money cleaning town centre toilets (can it become dirtier? More absurd for somebody with a PhD?) or working in a sex shop (I mean, as a shop assistant), I couldn’t but conduct a research study of sorts!

When I knelt down to the adage that no-one was bigger than bread, that was the type of jobs I started looking for. Perhaps the most interesting one I was seriously considering was as a tarot card reader, ‘training in Tarot provided’ provided you have some psychic abilities. I have an intuition and inner knowledge that are inexplicable to my rational mind. As a psychologist, I also have refined theories of what drives and scares most people. I might have been able to fake it. But out of respect for those with true skills, I held back.

A week or so into searching for a wild experiment, I was offered a (normal) consultancy contract which was all I could ask for – as a promise at the offer stage and as a reality once I was working on it. But my back-up plan of wild experiments still makes me super excited. I hope that next time when I need it, they don’t think me too old for that sex shop assistant vacancy!

30. Leaping high is far easier than climbing down.

I have probably applied for jobs under the level I was leaving in about half of the applications I submitted (yes, at the application stage, I broke my self-promises many times). I have been shortlisted for such a (part-time) job only once, and that was when I had explicitly written in the cover letter that my other part-time commitment was with the World Health Organization, which met enough of my money needs, and that I was interested in the learning potential of the post and in taking a break from “saving the world”.

From a certain professional level onwards, it is remarkably difficult, close to impossible, to become smaller than the measure that you have worked so hard to create.

31. The ones that work out will be easy.

I have spent up to a week on certain applications (ones that require a study design proposal) to lose by half a point to the competition, receive “we’ll keep you in mind for future opportunities” never-to-be-followed-up emails or even no response. The opportunities that materialised – where I accepted, not accepted, or accepted and then declined the offer (I am sorry again) – have, however, happened remarkably easily. Some of them involved nothing more than sending a ready CV and having an interview.

The only exception to this rule was my WHO commitment. It was a long and competitive process. Yet even that was ‘difficult’ with a disclaimer. My WHO profile and cover letter had been edited several times by then. The task I needed to complete within 24 hours was a normal task I would do in my day-to-day work. The two interviews were standard interviews and, as I mentioned, it was not as if I felt particularly brilliant in them.

I almost want to say that what will work out for you has been written in the stars, though you need to insist on the star-written message, none other allowed.

That said, a God-sent gift and a most natural outcome feel quite the same. In all those cases I felt super lucky – the right person at the right place at the right time. Yet I would also have moments of the ‘of course’ smirk creeping up my face. I earnt that. Both with the whole professional life I have had so far, every single day of effort of it, and the work I had done on getting a job, all the polishing of CVs and cover letters and reflecting on interview approach and attending webinars and what not, for far more days and far more months I would have expected in my worst unemployment nightmares.

32. You need clear-sighted targeting rather than bat-out-of-hell action.

The ease I have been talking about leads me to say that if you have a financial cushion, the last thing you need is to be applying for jobs as a bat out of hell. Even if you do not have a financial cushion, the intense action approach is pointless, but there is reassurance in pointless action. What ultimately works is the perfect fit, the easiest of things, the most natural step up and forward (I still mean a meaningful step. We are not talking about those that make you move from one foot to the other on the same spot). That perfect fit is what we need to wait for.

33. “One day it works out. It always works out.”

I hope that when ‘next time’ comes, I will be able stay in faith and avoid the lure of pointless action. I hope I remember more often the words of my colleague and friend Ben, which are amongst the most reassuring words I have heard in this period of changing sectors, doubling my income and moving by the seaside. They are almost too simple and too positive when you first hear them. But they are truer than anything on this list:

“One day it works out. It always works out.”

Just don’t fall apart before it does.

Thank you for reading!

Original published on LinkedIn, 21 Apr 2023. Last month a friend wrote, "I have referred back to your blog on ‘33 strong hypotheses ...’ a number of times recently as I have been job hunting and looking to make a career shift, and I find what you’ve achieved really inspiring!" I too needed to re-read it in a worryingly quiet period in my self-employed work (and was helped by it!). Version here is slightly edited and briefer.